Matt Black’s American Geography: A shallow representation of poverty

Rather than serve as a voice for impoverished communities, Matt Black’s book American Geography (2021) reveals a contempt for the population it purports to represent, and the work leans on shock value as a replacement for true engagement and empathy. The inconsistent photography, the confusing and overly-broad authorial intent, and lack of engagement with the context surrounding the book’s poverty leave the book as a shallow statement of unsurprising current-day facts (“people are poor across America”) instead of a deep engagement with the subject. When compared to other work that addresses the subject of impoverished communities, it is apparent that this project could have engaged at a deeper level to make a bolder, more interesting statement.

Poverty Safari vs Abstracted Narrative

The inconsistent style and quality of American Geography’s photos hurt the book’s ability to convey a cohesive message. The book alternates between what feels to me like a “poverty safari” and genuinely interesting abstract black and white texture work. The “poverty safari” works involve clearly-delineated human figures. These figures are sometimes up close in environmental portraits (candid or otherwise), and sometimes appear from farther away as part of a wider landscape. In the former category, none of the subjects appear at ease with the author; they are on edge, aren’t trusting, aren’t open. In the latter category, the images are interested only in conveying brokenness, isolation, and disrepair; further, some of the silhouette images are ineffective at conveying even those themes, with some of them being little more than the cheap “silhouetted figure walking on street” street style, with no clear tie between their formal characteristics and the theme of poverty. Sure, some of the streets and buildings are a little run down, but the images’ inclusion in this book force us to assume that the silhouetted figures are just as broken and destitute as the subjects we can see clearly, which upon reflection is an uncomfortable assumption to force the reader into making.

These photos come across to me as a “poverty safari”; the impression is that the author wandered these destitute towns until someone down on their luck wandered into the right location in the frame. With some exceptions (the old and withered hand on the fence post is a standout), these are photos of nouns: someone in dirty clothes in an empty street; a homeless man sitting in the far midground on an empty beach; a woman living in a shack and surrounded by junk. These are photos of the poverty, saying: This person is poor, look how unfortunate they are! They aren’t especially formally interesting (the square format doesn’t work for me here), they don’t educate the reader especially well (who hasn’t seen a homeless man sitting on the ground before?), and many of them are just uninteresting captures that scream “this town had nothing going on but I needed a picture.”

Where’s Black’s photography shines, though, is in the heavily abstracted images that are scattered throughout the book. When these photos feature people, which isn’t always, the hazily-visible people are more metaphor and stand-in than depictions of literal people in a literal location. These photos are much more thought provoking, and much less exploitive, than the much-greater volume of “documentary” photos which surround them. Perhaps the most effective example of these are plates 4 and 5 in the book: The juxtaposition of the two plumes of toxic-looking tire fire smoke filling the empty California farmland with the two abstracted cowboys at work and seen through a window.

Journalist or Artist? Inconsistent Authorial Intent

In the Fresno Bee’s video titled “Photojournalist Matt Black”, accessed on Feb 5 2024, Black says:

I see my role more or less as, like you say, as a reporter. And the idea is to report about this part of California, what’s going on in towns like this … It’s not about me, it’s about giving a voice to these towns, these communities, these people, that often don’t have one. So, through my photography I’ve been able to do that. And that’s what I see my role as doing.

However, the National Press Photographers Association has this to say in their Code of Ethics, also accessed on Feb 5 2024:

Editing should maintain the integrity of the photographic images' content and context. Do not manipulate images or add or alter sound in any way that can mislead viewers or misrepresent subjects.

Black’s photos are consistently heavily edited, even to the point of distraction. If Black sees his role as a reporter, then what news organization employs him? Who is formally holding him to journalistic ethics standards? The book makes no mention of a newspaper or other organization that sponsored the work. Why would a legitimate, professional, credentialed reporter say that he “sees [his] role more or less … as a reporter”?

On page 84 of the book, Black’s journal entry dated December 4, 2019 reads, in its entirety:

I walk to the Save-A-Lot grocery store for dinner. In line, I stand behind a large man in a black jacket buying a case of Mountain Dew, a box of powdered doughnuts, and a half gallon of chocolate milk. A local radio station playing over the store’s loudspeaker announces the day’s obituaries.

What is the reader supposed to take from this? What is the journalistic intent here? This reads as voyeuristic, as a lack of compassion, and as disgust on the part of the photographer. What is gained from presenting this vignette? Who is presented as being at fault? Why present this vignette? Is it to gawk at this disgusting, large man who’s apparently knowingly eating himself to an early death? Black declines to do the journalistic work of digging in beyond the surface level; the author has no intention of answering questions like, why is this man forced to sustain himself on junk food? What options are made available or not available to him? What choices of storefront locations have for-profit grocery stores made in this area? Especially telling: because this is a passing vignette, we don’t even know if the large man in the black jacket regularly eats like this! Maybe he’s celebrating a special event, or is treating himself, or is going to a party, or etc. etc. Black’s presentation of this vignette (“large man buys junk food”) juxtaposed with obituaries read from the store loudspeaker forces the reader to form a very specific opinion of this man, and Black wants us to feel bad about it.

This vignette forces us to call into question the intent of the photos appearing in the rest of the book. What assumptions are their framing and sequencing forcing us to make?

Photos of Nouns: Missing Context

The people in American Geography are poor people; they are not “people who are poor”. The geography of America, the book would have you believe, is made up of broken people who are all isolated from each other and simply find themselves in this state. The journal entries, which we’ve established are of suspect levels of empathy, sometimes make reference to extenuating circumstances, some bad turn of luck that has left someone down for the count, but stop there. There is no joy in Black’s representation of poverty, no dignity, no fight. There are vanishingly few families as subjects. Is that the complete life of an impoverished American? No parents accomplishing Herculean feats to put their children through college? No happy children, still-unaware of the wealth disparity they will soon find themselves on the wrong side of? No romance, sensuality?

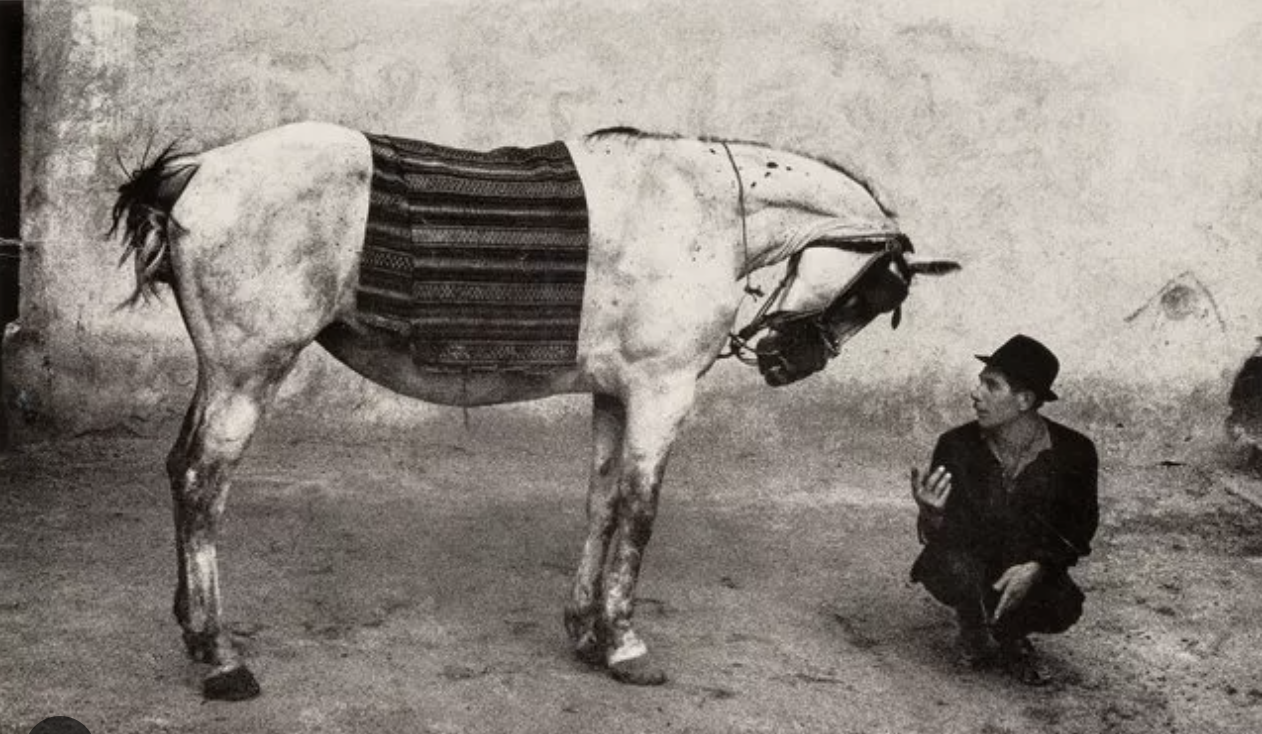

This book compares extremely unfavorably with two other works that also deal with poverty, exploitation, and mistreatment of their photographic subjects. Koudelka’s Gypsies presents that community as impoverished, but deep, full, and dignified, greatly prizing community, family and animals. Schutmaat’s Grays the Mountain Sends shows mining communities in the American West as having been tricked by the mining companies, lured in by the American dream, then dug up and gutted just like the mines themselves, and now left to make a life for themselves in what remains.

Where is Black’s attempt to deal with the poor in America as full and complicated people?

Conclusion

Black wants to be an artist: he wants to present heavily edited and abstracted photos that grab your eye, and he wants to tell a constructed story, a story about a permeating hopelessness and isolation that simply exists, is meant to be gawked at, and the liberal readers are intended to feel bad about it, pat themselves on the back for consuming “hard” media, and then go on with their lives. As an artist, Black wants to tell the story he wants to tell within his own parameters, and those parameters reveal an unpleasant impulse.

Black also wants to be a journalist: he wants to present himself as a reporter, get in people’s faces, present himself as reporting on a “story” that he’s done the legwork on. He wants the clout that the title “photojournalist” brings, without being formally held to those professional standards. He wants the edge of “reporting” on poverty.

At the end of the day, what has been accomplished by this book? Some people who are poor got their pictures taken so we can all feel bad about how poor they are, and the author gets to tell a gritty story at their expense. And that’s all.